Dan Gurney’s 1967 Champagne Week

story and photos by Eoin Young, edited by James Karthauser

It was a Champagne week for Daniel Sexton Gurney back in mid-summer 1967, when he won the Le Mans 24-hours for Ford one Sunday and was a winner again the next weekend when he took the laurels in the Belgian Grand Prix in his own Eagle.

|

| Dan Gurney prepares a surprise for the audience that would go on to unexpectedly start a tradition. Photo Courtesy of Dyler.com |

Dan Gurney was the first driver to spray the champers about rather than swigging it after he and A.J. Foyt had won at Le Mans. “I was so stoked that when they handed me the magnum of Moët I shook the bottle and began spraying at the photographers, drivers, Henry Ford II, Carroll Shelby and their wives. It was a very special moment.” Gurney made Champagne history when he sprayed the bubbly and the moment was captured on a special ‘Spray it Again, Dan’ fan poster.

|

| This classic moment was memorialized in this beautiful poster, 'Spray it Again Dan,' available at arteauto.com |

“What I did with the Champagne was totally spontaneous. I had no idea it would start a tradition. I was beyond caring and just got caught up in the moment. It was one of those once-in-a-lifetime occasions where things turned out perfectly...I thought this hard-fought victory needed something special.” “LIFE” photographer Flip Schulke, was a popular chap on the racing scene and Dan had hauled him up on to the stage before he started spraying the Champagne. “I took one photo and then ducked,” Schulke recalled. “When it was over Dan handed me the empty bottle and autographed it.

|

| AJ Foyt (right) and Dan Gurney (left) on victory stand. Photo Courtesy of Ford Archive |

That original Moët Champagne bottle is now in pride of place in the conference room at All American Racers headquarters. Schulke had converted it to a table lamp and used it in his Florida home for 30 years before returning it to Gurney with the comment “You did it...you should have it!” Dan and Evi removed the lampshade, took the electrics out, and had a special glass case made to preserve the famous bottle.

|

| Ford Mk IV winning at Le Mans 1967. Photo Courtesy of All American Racers |

Gurney and Foyt drove their way into Le Mans history with the red 7-litre Mk IV Ford, specially modified with a bump on the roof to accommodate the lanky Dan. They raised the race record by 10mph to 135mph average for the 24 hours, covering a total of 3,250 miles. It was also the first time that an American car and driver combination had won at Le Mans.

|

Dan Gurney takes the chequer to win the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa in 1967 in his Eagle-Westlake V12.

Photo Courtesy of All American Racers

|

Dan won at Spa in his own 3-litre V12 Eagle- Weslake. The 3-litre Cosworth-Ford V8s had arrived to win first time out at Zandvoort in Jim Clark’s works Lotus 49, and the two new cars bracketed the Eagle on the front row at Spa. Clark stormed into an immediate lead with Jackie Stewart second in the unloved H16 BRM with Gurney third. Gurney was moving in on Stewart when Clark pitted with a blown spark plug and Gurney also stopped to warn of fluctuating fuel pressure but there was nothing the crew could do so he was sent back out, now in second place, 16sec behind Stewart. Dan was now in attack mode, lowering the lap record as he chased down Stewart and went into the lead with seven laps left.

It was Moët that Dan sprayed in those days and it was Moët that was presented at races thereafter on a gratis basis, Moët et Chandon presumably figuring that giving their bubbles free was financial involvement enough. But Bernie Ecclestone decided that ‘free’ was a word with which he was uncomfortable. He put the naming rights for the official alcoholic fizz in Formula 1 up for bids, and G.H. Mumm won.

|

| Dan Guarney at speed on the way to winning the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa. Photo Courtesy of All American Racers |

Mays had been winning sprints and hillclimbs with the elegant lightweight Type 13 Bugattis that were in production from 1910 to 1926. In the 1930s Mays would create the ERA (English Racing Automobiles) racing marque and in the late 1940s he was the man behind BRM (British Racing Motors). The first BRM was a screaming 1500cc V16 which sounded far better than its racing record would read but a BRM would win the 1962 World Championship in the hands of Graham Hill. Gurney had a dismal summer with BRM in 1960 with a best result of 10th at Silverstone.

In a 1973 interview, Mays told me the story about dining with his engineer friend, Amherst Villiers, in a London restaurant in 1923 when a Champagne label caught his eye. “I had just won a speed trial in the Bugatti and we were celebrating over dinner with a bottle of Champagne. It occurred to me that the striking red and gold Cordon Rouge label on the bottle was just what I needed as a racing name for my Bugatti, and I suppose that was really where sponsorship in racing started.” At the time of the interview, Mays was 73 and still active as Director of Racing for the Marlboro-BRM team.

That night in 1923, Mays asked the waiter if he could steam the label off the bottle as a guide for the name to be painted on the bonnet of his Bugatti and he wrote to the head office of the G.H. Mumm Champagne company, makers of Cordon Rouge in Reims, asking for their permission for him to borrow their brand name for his French racing car. The company replied immediately, delighted with the idea, and despatched three cases of Champagne to toast their new association with success.

Pleased with this double result from the bubbly company, Mays wrote to the makers of Cordon Bleu Cognac but while he received permission to use the name on his ‘other’ Brescia, he was never offered any brandy!

In fact this was inadvertently a first venture into the world of commercial sponsorship in motorsport that has led to the wheel turning full circle. Cordon Rouge Champagne is now the official bubby in Grand Prix racing for presentation and spraying on the Formula 1 rostrums.

Tom Wheatcroft arranged with Raymond Mays to open his motor racing museum at Donington Park in 1974, linking with the UK importers of G.H. Mumm Champagne – half a century after Mays ‘discovered’ the label – and the bubbles started spraying in vintage racing circles with a replica of a Brescia Bugatti used in major store promotions. A special Cordon Rouge Classic Bugatti hillclimb was held by the Bugatti Owners’ Club at Prescott on June 2, 1974 and the winner at six vintage meetings during the summer was presented with a Jereboam of Cordon Rouge and each finisher received a bottle.

Cordon Rouge Champagne had already been the toast of society for half a century when Mays, the young Cambridge graduate made racing history by being the first to carry what amounted to a commercial sponsor’s name on his racing car. That the ‘sponsor’ was a top Champagne company only added to the flair of Mays’ talent as a racing driver. With ‘Cordon Rouge’ he was to dominate speed trials and hillclimbs all over England during the summer of 1924.

Mays, the son of a prominent wool brokerage family from Bourne, Lincolnshire, leapt to prominence in speed events in 1921, while still at Cambridge. He drove a speed model Hillman in those days and had such instant success that he invested everything in a new Brescia Bugatti for the 1922 season. Once again he excelled and during 1923 the Bugatti was run in much modified trim. The speed and engineering so impressed Ettore Bugatti that Mays was provided with a second Brescia for the season of 1924, thus providing him with the need to differentiate between his two Bugattis.

The Brescia was a 1500cc 16-valve 4-cylinder sporting car, the competition models being Type 13s in the Bugatti numbering system. They won the voiturette race at Brescia in 1921 to earn the title and Mays made his debut with his Brescia at the Laindon hillclimb, facing Leon Cushman and Eddie Hall in similar cars and placed second in his class. By the end of the 1922 season Mays and the striking blue-grey Bugatti had become extremely competitive. During the winter of 1922-23 Mays began a modification programme on the Bugatti working with Amherst Villiers, a brilliant engineering friend from Cambridge days. Mays wanted a ‘super hillclimb car’ and Villiers designed new pistons and camshaft and made other modifications to boost the Bugatti’s engine from a rev limit of 4300rpm to over 6000rpm – an almost unheard of figure in those days. Running specially-brewed RD2 alcohol fuel – it cost over six shillings a gallon in those days which was regarded as insanely expensive – Mays found that he had the super-car he wanted, but there were development problems with bearings.

Villiers was also an accomplished painter having produced portraits of subjects as diverse as Graham Hill and James Bond creator, Ian Fleming. It was Villiers who designed a fictional car to the fit the role of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang which Fleming was using as the theme for a children’s book. His painting of Mays at speed in the Brescia Bugatti was used by G.H. Mumm in a presentation and a poster for the Prescott Hillclimb that summer.

M. Lefrere in Bugatti’s London agency, was most impressed and at the Show he gave Mays a personal letter of introduction to Le Patron, Ettore Bugatti. Bugatti invited the young Englishman to the Molsheim factory, emphasising that he bring his Brescia with him.

Mays senior was delighted at his son’s newfound success and financed the trip to Molsheim, taking the modified car for Bugatti’s inspection. Ettore stood worked long and hard on the cars, Mays helping on evenings away from the wool business. Bleu was potentially faster than Rouge with its later engine, but it mixed success with misfortune, winning at South Harting and throwing a rear wheel at Caerphilly. After this hair-raising ‘moment’ the car was set aside for axle shaft changes, while Rouge howled from strength to strength, winning all over the country.

The Brescia Bugattis finally ran out of hours and engines and Mays moved on but he had brought Champagne and sponsorship to motor racing, making history as he did so. Dan Gurney might have been the first driver to spray the crowd after a race win in 1967, but Bernie Ecclestone made an extra little bit of history, whether he realised it or not, by bringing Cordon Rouge back into the motorsport winner’s circle!

We here at l'art et l'automobile hope that your holiday season has been filled with laughter and joy, and if you're of the particular frame of mind, filled with champaign toasts and the occasional dousing. We hope you have enjoyed this little taste of Racing History, and that your spirits rise like the bubbles from the champaign flutes.

We also wish to toast Dan Gurney, who's accomplishments and exploits have not only gone down in racing history, but who's jovial spirit and gleeful nature have given us a much lauded tradition that racers still honor and celebrate to this day.

Cheers to Dan and Cheers to you this holiday season!

Jacques Vaucher

Remember we have a wide variety of items in our gallery, so do not hesitate to contact us if you are looking for something in particular.

And as always, be sure to Like and Share on Facebook, Follow us on Twitter, share a photo on Instagram and read our Newsfeed.

In a 1973 interview, Mays told me the story about dining with his engineer friend, Amherst Villiers, in a London restaurant in 1923 when a Champagne label caught his eye. “I had just won a speed trial in the Bugatti and we were celebrating over dinner with a bottle of Champagne. It occurred to me that the striking red and gold Cordon Rouge label on the bottle was just what I needed as a racing name for my Bugatti, and I suppose that was really where sponsorship in racing started.” At the time of the interview, Mays was 73 and still active as Director of Racing for the Marlboro-BRM team.

That night in 1923, Mays asked the waiter if he could steam the label off the bottle as a guide for the name to be painted on the bonnet of his Bugatti and he wrote to the head office of the G.H. Mumm Champagne company, makers of Cordon Rouge in Reims, asking for their permission for him to borrow their brand name for his French racing car. The company replied immediately, delighted with the idea, and despatched three cases of Champagne to toast their new association with success.

Pleased with this double result from the bubbly company, Mays wrote to the makers of Cordon Bleu Cognac but while he received permission to use the name on his ‘other’ Brescia, he was never offered any brandy!

In fact this was inadvertently a first venture into the world of commercial sponsorship in motorsport that has led to the wheel turning full circle. Cordon Rouge Champagne is now the official bubby in Grand Prix racing for presentation and spraying on the Formula 1 rostrums.

Tom Wheatcroft arranged with Raymond Mays to open his motor racing museum at Donington Park in 1974, linking with the UK importers of G.H. Mumm Champagne – half a century after Mays ‘discovered’ the label – and the bubbles started spraying in vintage racing circles with a replica of a Brescia Bugatti used in major store promotions. A special Cordon Rouge Classic Bugatti hillclimb was held by the Bugatti Owners’ Club at Prescott on June 2, 1974 and the winner at six vintage meetings during the summer was presented with a Jereboam of Cordon Rouge and each finisher received a bottle.

Cordon Rouge Champagne had already been the toast of society for half a century when Mays, the young Cambridge graduate made racing history by being the first to carry what amounted to a commercial sponsor’s name on his racing car. That the ‘sponsor’ was a top Champagne company only added to the flair of Mays’ talent as a racing driver. With ‘Cordon Rouge’ he was to dominate speed trials and hillclimbs all over England during the summer of 1924.

Mays, the son of a prominent wool brokerage family from Bourne, Lincolnshire, leapt to prominence in speed events in 1921, while still at Cambridge. He drove a speed model Hillman in those days and had such instant success that he invested everything in a new Brescia Bugatti for the 1922 season. Once again he excelled and during 1923 the Bugatti was run in much modified trim. The speed and engineering so impressed Ettore Bugatti that Mays was provided with a second Brescia for the season of 1924, thus providing him with the need to differentiate between his two Bugattis.

|

| Raymond Mays in the Cordon Rouge Brescia Bugatti. Photo Courtesy of All American Racers |

Villiers was also an accomplished painter having produced portraits of subjects as diverse as Graham Hill and James Bond creator, Ian Fleming. It was Villiers who designed a fictional car to the fit the role of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang which Fleming was using as the theme for a children’s book. His painting of Mays at speed in the Brescia Bugatti was used by G.H. Mumm in a presentation and a poster for the Prescott Hillclimb that summer.

M. Lefrere in Bugatti’s London agency, was most impressed and at the Show he gave Mays a personal letter of introduction to Le Patron, Ettore Bugatti. Bugatti invited the young Englishman to the Molsheim factory, emphasising that he bring his Brescia with him.

Mays senior was delighted at his son’s newfound success and financed the trip to Molsheim, taking the modified car for Bugatti’s inspection. Ettore stood worked long and hard on the cars, Mays helping on evenings away from the wool business. Bleu was potentially faster than Rouge with its later engine, but it mixed success with misfortune, winning at South Harting and throwing a rear wheel at Caerphilly. After this hair-raising ‘moment’ the car was set aside for axle shaft changes, while Rouge howled from strength to strength, winning all over the country.

|

| Dan Gurney with the original Moët bottle in the All American Racers’ boardroom. |

We here at l'art et l'automobile hope that your holiday season has been filled with laughter and joy, and if you're of the particular frame of mind, filled with champaign toasts and the occasional dousing. We hope you have enjoyed this little taste of Racing History, and that your spirits rise like the bubbles from the champaign flutes.

We also wish to toast Dan Gurney, who's accomplishments and exploits have not only gone down in racing history, but who's jovial spirit and gleeful nature have given us a much lauded tradition that racers still honor and celebrate to this day.

Cheers to Dan and Cheers to you this holiday season!

Jacques Vaucher

Remember we have a wide variety of items in our gallery, so do not hesitate to contact us if you are looking for something in particular.

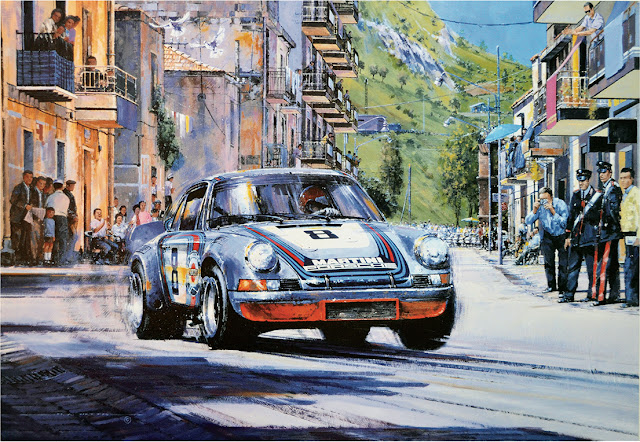

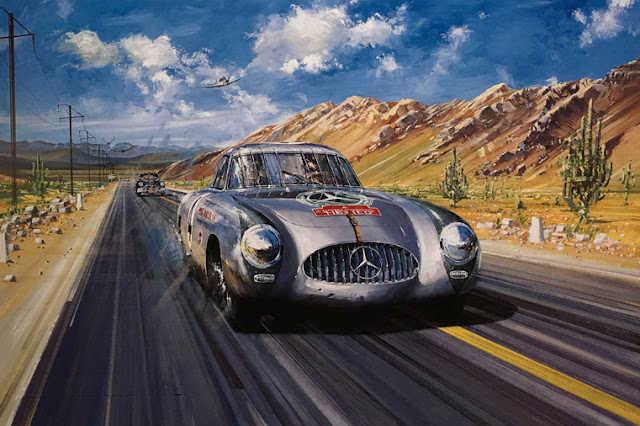

And as always, be sure to Like and Share on Facebook, Follow us on Twitter, share a photo on Instagram and read our Newsfeed.