For over 70 years, Formula One has been a premier global sport, with opulent, multi-day races held in countries across the world.

— everywhere, that is, except for the United States. But that could be changing sooner than most think.

Since its founding, Formula One has been an international organization.

was held in 1950 at Silverstone in the United Kingdom. The winning driver, Italian racer Giuseppe Farina, drove a supercharged Alfa Romeo in front of 120,000 cheering spectators — including England’s reigning monarch, King George VI.

That European race set the stage for Formula One’s global presence, excluding America.

Headwinds in America

|

Formula One has a storied history in the United States. Mario Andretti sat on the pole for his first

F1 start at Watkins Glen in 1968. Photo By Lat Photographic |

|

Logistically, it’s hard to be a Formula One fan in America. Most of the races take place in Europe, so watching live events often means waking up at the crack of dawn. The U.S. also has its own motor sports to watch like IndyCar and NASCAR, which has been around since the 1940s.

Peter Habicht is the founder of Formula One's largest fan group in America, located in San Francisco. The group has about 2,500 members.

“We have a difficult time following a lot of the European races because they go on at about five in the morning, so it’s a challenging proposition to get a group together, usually at a sports bar, to watch a live start of a race,” said Habicht.

Unlike basketball or football, Formula One racing provides very few American drivers to cheer on: The

last American to win a race was Mario Andretti, and that was at the Dutch Grand Prix in 1978.

“The sport, under prior stewardship, began to move wherever the money was the highest," said Leo Hindery, InterMedia Partners managing partner and a former race car driver.

"And that left Formula One in places like Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Bahrain, Abu Dhabi, Singapore, Shanghai, none of which is bad for the sport except for in the process of doing that, they neglected to maintain a footprint here in the United States,” said Hindery, a Formula One promoter.

In 2005, the U.S. Grand Prix didn't turn out as Formula One might have hoped.

Media reports at the time called it a disaster. At the very last minute, fourteen cars were forced to withdraw due to safety concerns. Most fans left the event feeling disappointed and cheated of their money. The race they’d come to see didn’t deliver.

“It was a low point, for sure, in American Formula One history,” said Habicht.

Improving relations with the US

|

| Ayrton Senna leads the field at the United States Grand Prix at Phoenix in 1989. Photo By Lat Photographic |

Still, the future of Formula One in America may be getting brighter. Competitor NASCAR has had an

undeniably rough few years, which could be a boon for Formula One. More importantly, Formula One has had a

significant change in leadership: In early 2017, it was acquired by Liberty Media, a U.S. company, for $8 billion.

Formula One’s new CEO, Chase Carey, has high hopes for the sport in America,

telling CNBC at the time of the acquisition that he wanted to make the races feel more like Super Bowl events with mobile content, and behind-the-scenes access available for fans.

“Put an organization in place that lets us make these events everything they can be, reaches out across digital media that we're not connecting to today [and] build a marketing organization that connects to fans [and] enables fans to connect to the sport,” said Carey.

One year later and

expansion in America is already happening: a new Miami street circuit Grand Prix will be added to the calendar in 2019. The race would be in addition to the U.S. Grand Prix. Hindery predicted there will be a race in the Northeast, possibly New Jersey, within the next two to three years as well.

America's untapped market

|

Fans greet racer Lewis Hamilton of Mercedes and Great Britain during the United States Formula One

Grand Prix in 2017. Photo courtesy of CNBC |

There’s a lot of

money to be gained from ticket sales, advertisers and sponsors in America. U.S. consumers shelled out $56 billion to attend sporting events in 2016, according to

a study by CreditCards.com.

“You have 325 million people in the United States which, just in sheer numbers, is an audience you shouldn’t leave behind,” explained Hindery.

Formula One could use the economic boost. In 2012, FinanceAsia, a Hong Kong-based financial news publication,

reported Formula One's valuation was $9.1 billion. That means over the four-year period between that valuation and the subsequent $8 billion purchase, it lost 12 percent of its value.

However, it’s not a sure thing that Formula One will catch on in the States. U.S. Grand Prix attendance

fell in 2017 by 4.4 percent from the year prior. And there are

no American drivers racing in Formula One this year.

But if there’s ever a time for Formula One to capture America’s hearts, it’s now. With NASCAR struggling and new American F1 leadership, it’s possible the pastime can make a permanent mark on U.S. soil.

On Sunday October 22nd, Formula 1 returns to the U.S. for the first time with the U.S. Grand Prix in Austin, Texas, at the brand new, world-class race track, the Circuit of the Americas. Having resumed Formula 1 racing in 2007, bringing the sport back to the U.S. for the first time since 2007 at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, this race should be an enormous boon to the push for the sport in America.

Although F1 has had a long and at times troubled relationship with the American market, the sport also has a rich history here. Since 1950, the U.S. has hosted 62 F1 events, including races at Watkins Glen, Sebring, the streets of Detroit and several others. As some F1 fans prepare to head to Austin while others plan to watch the U.S. Grand Prix on television, here's a quick recap of F1 racing's American history.

1950-1960—Indianapolis 500: OK, technically this was not a traditional Formula One race, let alone a road-course race. But 11 times from 1950-1960, the Indianapolis 500 counted as a round of the world championship, with points scored at Indy adding to F1 drivers' season tally.

1959—Sebring: In 1959, the U.S. hosted two F1 races for the first time. In addition to the Indy 500, F1 added the United States Grand Prix to its schedule. The race, held at Sebring International Raceway in Florida, was the ninth and final round of the 1959 season.

1960—Riverside: In 1960, the United States Grand Prix moved from Sebring to the famous—and today much missed—Riverside International Raceway in Riverside, Calif. Promoters had a difficult time drumming up interest for the Sebring race the previous year, and had similar problems with the Riverside race. It wasn't until the following year when F1 moved to Watkins Glen International in upstate New York that American fans started to embrace Grand Prix racing.

1961-1980—Watkins Glen: After running the United States Grand Prix at two different venues in 1959 and 1960, the event finally found a somewhat permanent home in 1961. Originally, Daytona International Speedway was supposed to host the 1961 event, but an agreement couldn't be made. In the end, F1 went to Watkins Glen, where it remained for almost 20 years.

1976-1983—Long Beach: After a 16-year hiatus, F1 returned to the West Coast in 1976. Dubbed the United States Grand Prix West, the race found a home in Long Beach for seven seasons. The Long Beach races also marked the first time a city street circuit was used in the U.S., and the event is credited with having a major impact on turning the city around and increasing its desirability as a place to live. Of course, when F1 left after the 1983 race, Long Beach continued to host the CART World Series, and today hosts the Izod IndyCar Series and American Le Mans Series. But it was F1 that started the city's ongoing affair with auto racing.

1981-1982—Las Vegas: F1 left Watkins Glen after the 1980 running of the United States Grand Prix. The U.S. did continue to host the final race of the F1 season, but in Las Vegas. For two seasons, F1 participated in the Caesars Palace Grand Prix, which featured a surprisingly decent—if rather flat—track layout in the parking lot of the famous Las Vegas hotel. When F1 did not return to Las Vegas, the CART World Series added the race to its schedule in 1983 and 1984.

1982-1988—Detroit: The year 1982 marked the first and only time that three F1 races have appeared in the United States during a single season. In addition to races in Long Beach and Las Vegas, downtown Detroit hosted its own street race. The circuit was bumpy—no surprise to Michigan drivers—tight and demanding. Alas, F1 could not come to an agreement with the host city for 1989, whereupon CART once again added Detroit to its schedule.

1984—Dallas: Although this weekend's U.S. Grand Prix marks F1's first visit to Austin, the series is no stranger to Texas. In 1984, Fair Park in Dallas was converted to an F1 circuit to host the Dallas Grand Prix. The race turned out to be a one-off event, and it was plagued when high ambient temperatures caused the track surface to break apart. Drivers said it was the roughest circuit they had encountered, and the race was a significant physical challenge for the Grand Prix aces. Keke Rosberg won the race, but Nigel Mansell put on a memorable show by hitting a wall on the final lap, coming to a stop and attempting to push his car over the finish line. Instead he collapsed, exhausted by the heat on the rough circuit.

1989-1991—Phoenix: After the final race in Detroit in 1988, F1 wanted a new venue. It came down to either Laguna Seca in California and the streets of Phoenix, and Phoenix got the nod. From 1989-1991, the United States Grand Prix found its home in Arizona, and the first event, held in June, roasted drivers and spectators with temperatures exceeding 100 degrees. The organizers learned a lesson; Phoenix's next two races were held in March.

1992-1999—Hiatus: There were no F1 races held in the U.S. during this time period, and some began to wonder if the sport would ever return. And then along came Indianapolis . . .

|

| The 2007 United States Grand Prix at Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Photo By Lat Photographic |

2000-2007—Indianapolis: After a nine-year absence, F1 came back to the U.S. in a huge way and to much fanfare in 2000. The series returned to its American roots, racing at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, after then-Speedway boss Tony George invested millions to build a road course inside the world-famous oval. Not only that, but George dropped millions more to construct modern F1-spec garages, offices and a new pagoda and media center on the oval's front straight.

That first year, in 2000, the venue offered the largest F1 crowd in history as more than 250,000 fans flooded the giant facility, and it looked like a smash hit that would cement the series in the U.S.

However, the race—and F1 in particular—suffered major backlash in 2005 when cars using Michelin tires were forced to withdraw due to concerns their tires would fail on the Speedway's banking. With 14 entries using Michelins, that left only six cars on Bridgestone tires to start the race. Fans were not impressed.

Still, Indy hosted two more races, and though the crowds fell off significantly, the attendance was still strong compared to other F1 events around the world. Nevertheless, George found F1 boss Bernie Ecclestone's financial demands for 2008 too high to make a profit, and the U.S. bid goodbye to Grand Prix racing yet again.

U.S. Grand Prix Winners

2007, Indianapolis: Lewis Hamilton, McLaren-Mercedes

2006, Indy: Michael Schumacher, Ferrari

2005, Indy: Michael Schumacher, Ferrari

2004, Indy: Michael Schumacher, Ferrari

2003, Indy: Michael Schumacher, Ferrari

2002, Indy: Rubens Barrichello, Ferrari

2001, Indy: Mika Häkkinen, McLaren-Mercedes

2000, Indy: Michael Schumacher, Ferrari

1991, Phoenix: Ayrton Senna, McLaren-Honda

1990, Phoenix: Ayrton Senna, McLaren-Honda

1989, Phoenix: Alain Prost McLaren-Honda

1988, Detroit: Ayrton Senna, McLaren-Honda

1987, Detroit: Ayrton Senna, Lotus-Honda

1986, Detroit: Ayrton Senna, Lotus-Renault

1985, Detroit: Keke Rosberg, Williams-Honda

1984, Dallas: Keke Rosberg, Williams-Honda

1984, Detroit: Nelson Piquet, Brabham-BMW

1983, Detroit: Michele Alboreto, Tyrrell-Ford

1983, Long Beach: John Watson, McLaren-Ford

1982, Detroit: John Watson, McLaren-Ford

1982, Las Vegas: Michele Alboreto, Tyrrell-Ford

1982, Long Beach: Niki Lauda, McLaren-Ford

1981, Las Vegas: Alan Jones, Williams-Ford

1981, Long Beach: Alan Jones, Williams-Ford

1980, Long Beach: Nelson Piquet, Brabham-Ford

1980, Watkins Glen: Alan Jones, Williams-Ford

1979, Long Beach: Gilles Villeneuve, Ferrari

1979, Watkins Glen: Gilles Villeneuve, Ferrari

1978, Long Beach: Carlos Reutemann, Ferrari

1978, Watkins Glen: Carlos Reutemann, Ferrari

1977, Long Beach: Mario Andretti, Lotus-Ford

1977, Watkins Glen: James Hunt, McLaren-Ford

1976, Long Beach: Clay Regazzoni, Ferrari

1976, Watkins Glen: James Hunt, McLaren-Ford

1975, Watkins Glen: Niki Lauda, Ferrari

1974, Watkins Glen: Carlos Reutemann, Brabham-Ford

1973, Watkins Glen: Ronnie Peterson, Lotus-Ford

1972, Watkins Glen: Jackie Stewart, Tyrrell-Ford

1971, Watkins Glen: Francois Cevert, Tyrrell-Ford

1970, Watkins Glen: Emerson Fittipaldi, Lotus-Ford

1969, Watkins Glen: Jochen Rindt, Lotus-Ford

1968, Watkins Glen: Jackie Stewart, Matra-Ford

1967, Watkins Glen, Jim Clark, Lotus-Ford

1966, Watkins Glen: Jim Clark, Lotus-BRM

1965, Watkins Glen: Graham Hill, BRM

1964, Watkins Glen: Graham Hill, BRM

1963, Watkins Glen: Graham Hill, BRM

1962, Watkins Glen: Jim Clark, Lotus-Climax

1961, Watkins Glen: Innes Ireland, Lotus-Climax

1960, Riverside: Stirling Moss, Lotus-Climax

1959, Sebring: Bruce McLaren, Cooper-Climax

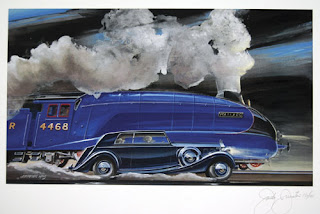

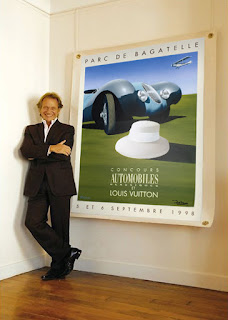

At l'art et l'automobile, we are Formula 1 fans of a ravenous nature, and wish to celebrate our love of the sport with you, as well as to assist you in your collecting of Formula 1 artwork and memorabilia.

Enjoy looking through the collection and tell us which ones you would like to own. Please Tour the gallery at

arteauto.com, and perhaps add a piece to your collection.

Enjoy the Race,

Jacques Vaucher

For more great automotive artwork and memorabilia, don't forget to browse the many other categories on our

WEBSITE. Remember we also have many more items in our gallery, do not hesitate to contact us if you are looking for something in particular.

And as always, be sure to Like and Share on

Facebook, Follow us on

Twitter, share a photo on

Instagram and read our

Blogs.