It was this innovation—not the Model T itself—that cemented the automobile's future.

Originally Published April 2013 by Tony Swan, edited by James Karthauser

When modern drivers think about the Ford Model T—if they think about it at all—they perhaps dimly perceive it as the car that changed the world. That is correct, of course, as far as it goes. But this month, the Ford Motor Company is quietly commemorating a T-related centennial that was the true source of that seismic shift in mobility: the automotive assembly line. The Model T just happened to be the product it was used to build.

Indeed, the innovations could very well have been made by some other company and involved some other car. But in April 1913, led by production boss Charlie “Cast Iron” Sorensen, Ford began taking its first tentative steps toward a moving line that used conveyor belts to stream components past workers who performed one or two tasks each. This pioneering manufacturing process made automobiles affordable to just about anyone and became the template for the entire industry.

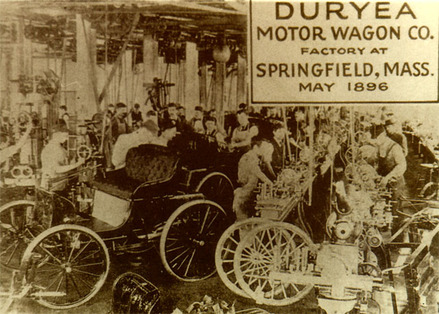

Prior to 1913, Ford and virtually every other automaker assembled whole cars at a station with a team of workers working together to complete a single example, usually from start to finish. Like other companies, Ford had made numerous refinements to the process, achieving impressive production totals at the Piquette Avenue plant where the Model T was born in October 1908.

When deciding to implement the assembly line, neither Sorensen nor Henry Ford nor anyone else involved had the benefit of time-motion studies. They simply reasoned that moving the component at a fixed rate past each station would reduce the number of workers required to build the cars, reduce the time required for assembly, increase volume, and allow the company to control the pace.

The guinea pig was the T’s magneto, a component that supplied ignition energy to the engine before generators became common. A complex and innovative component that was one of the early Model T’s technological advantages, Ford’s magneto was integrated with the engine’s flywheel and involved many pieces. Under the old system, each magneto was assembled by one worker. On average, that worker could assemble 35 of them in a nine-hour shift, or roughly one every 15 minutes.

After some tinkering with the line rate and other factors, Sorensen and his cohorts achieved results that were probably startling even to them. Starting with 29 workers performing 29 different tasks, the experiment reduced assembly time by about seven minutes per unit. And with more refinements, Sorensen was able to reduce the magneto-line workforce to 14 and cut assembly time to five minutes.

FULL SPEED AHEAD

It didn’t take long for Sorensen to apply the moving-line principle to all aspects of Model T production. Engine assembly time was cut from almost 10 hours to less than four. The team tackled chassis assembly in August and quickly cut completion time from 12 hours to six. It was down to slightly less than three hours by October, then to 2.3 in December.

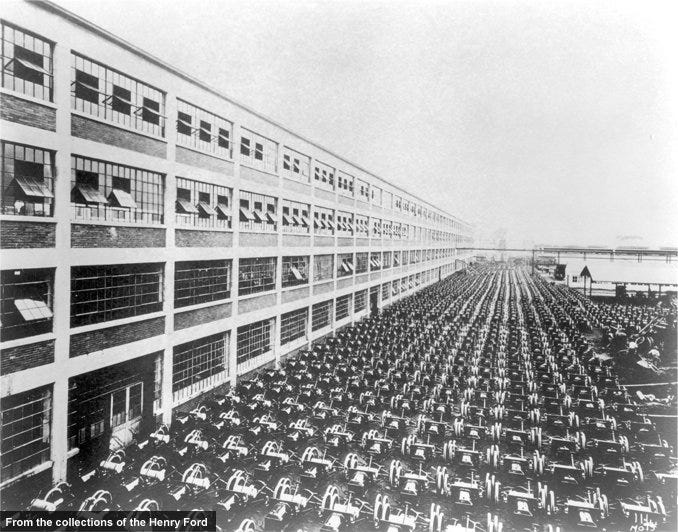

By October, Ford’s vast plant in Highland Park, Michigan, was a maze of conveyors, powered drive belts, overhead traveling cranes, and hundreds of machine tools. Moving assembly went into full swing. And the efficiencies established on a small scale with the magneto line translated directly to total production, which exploded.

Four years prior, while construction crews were at work on the gigantic Highland Park facility, the Piquette work teams assembled 10,660 Model Ts, keeping Ford atop the manufacturing standings ahead of Buick. In Highland Park’s immense spaces, production for 1910 rose to 19,050, despite various hiccups associated with settling into the new facility. By 1912, output was up to 68,773.

But those numbers were dwarfed by the results of the moving assembly line. The process netted 170,211 examples in 1913, 202,667 in 1914, well over half a million in 1916, and 735,020 in 1917. All U.S. industrial output was down in 1918, a casualty of the final year of World War I, as well as the economic downturn that followed in its wake. But the market rebounded in 1920, and Model T production topped one million cars for the first time, at 1,301,067. Output peaked at 2,011,125 in 1923, followed by almost two million units in 1924 and ’25 before demand finally began to tail off.

Verging on obsolescence and dowdy compared with many competitors, the T finally went out of production on May 26, 1927. Although final tallies vary, the generally accepted total stands at just over 15 million built.

THE PAYOFF

Henry Ford’s much publicized Model T mission was to “build a car for the great multitude,” and the key to the quest was economies of scale, making the car affordable to as many potential customers as possible.

When the car made its debut, it was innovative, simple, rugged, and easily repaired by owners with even modest mechanical skills. But it wasn’t exactly cheap: $825 for a basic Runabout, the least expensive model, and $850 for the five-passenger Touring version. The pricing didn’t include extras such as a top or side curtains and actually increased to $900 and $950 for 1910.

But as production numbers soared, the prices went down. Ford charged $600 in 1913 for a Touring T, $440 in 1915, and $360 in 1917. Pricing bottomed out at $290 for a 1925 Touring model (the Runabout cost $30 less) and ramped up slightly in the last year and a half of the Model T’s long life.

The assembly innovations at Highland Park did not go unnoticed. The multiple buildings of Ford’s big facility regularly welcomed visitors, and it wasn’t long before competitors began adopting the techniques developed there. So by the end of the Model T’s 19-year run, it was fair to say that Ford really had put the world on wheels.

THE $5 DAY AND SOCIAL CHANGE

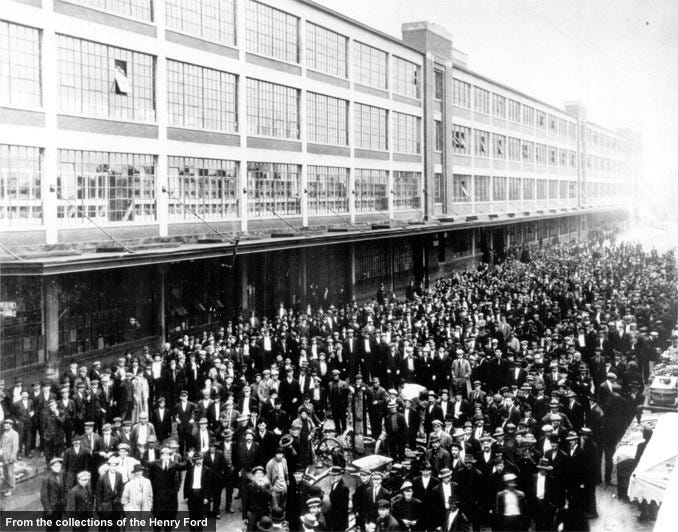

One of the more noteworthy chapters in the moving-assembly story was Ford’s announcement on January 5, 1914, that the company was increasing its wage rate to $5 per eight-hour workday—more than double the existing rate for the then-standard nine-hour day.

Ford was already racking up huge profits, and the new policy could be interpreted as altruistic, although other automakers received the news with clenched jaws. There was open speculation that Henry was only aiming to ensure that his workers could afford to buy the products they were assembling.

But Ford’s motives were far more pragmatic. Assembly-line work—performing the same tasks every day for long hours at a stretch—was mind-numbingly dull, and the company found itself beset with unacceptable turnover in its labor pool. In 1913, for example, Ford was forced to hire more than 52,000 workers to sustain a workforce of about 14,000.

There were strings attached to that $5 bill. The basic wage was $2.34. To qualify for the additional $2.66, a worker had to meet company standards for clean living, including sobriety, no gambling, thrift, and a happy home environment. Ford actually formed a sociological department whose staff members visited homes to assess workers’ worthiness for the full five bucks.

That policy would provoke torch-bearing mobs and militant picket lines today, but it was acceptable in 1914 and produced dramatic reductions in absenteeism and turnover. Moreover, the $5 day attracted job seekers from all over the country, particularly the South, permanently changing the demographics of Detroit.

Other changes were even more profound. The availability of an affordable, durable automobile put the dream of unlimited personal mobility within reach of a broad swath of society, setting the stage for the rise of the suburbs and the establishment of a national highway network. Automobiles were no longer a novelty when the Model T made its first appearance, but they were far from universal. By the time the last T left the line, the automobile was fully integrated into everyday life, and the world would never be the same.

Model T Myths

The Model T moving assembly was Henry Ford’s idea. Not really. As production honcho Charlie Sorensen observed in his memoirs, “Henry Ford is generally regarded as the father of mass production. He was not. He was the sponsor of it. Mr. Ford had nothing to do with originating, planning, and carrying out the assembly line. He encouraged the work. His vision to try unorthodox methods was an example to us.”

All Model Ts were black. Not true. The “any color you want, as long as it’s black” ethic began in 1913. Folklore says the black color was a Japanese lacquer chosen for its fast-drying properties. Also not true. The black paint was cheaper and more durable. Ford restored colors to the Model T palette in 1926.

The Model T was all-new. Not quite. It was innovative and included the extensive use of vanadium steel, which was stronger and lighter than ordinary steel; an integrated flywheel/magneto; and a monoblock four-cylinder engine with a removable cylinder head. It was also lightweight, at about 1200 pounds. But for all that, it was an evolution of the highly successful Model N (1906–08).

|

| 1913 – Ford Highland Park Plant- First Moving Assembly Line, Photo courtesy of Western Slope Auto.com |

The Model T never changed. Wrong. Ford made a number of mechanical and cosmetic running changes to the T over the years, including the introduction of safety glass in 1926, an industry first. But the Model T failed to change in key ways. It retained its two-speed planetary transmission long after competitors were offering three-speed gearboxes with shift levers, the cooling system was via thermosyphon (meaning no water pump), and electric starting wasn’t even an option until 1919.

The Model T was hard to drive. Quite the opposite. Compared with other cars of the day, it was easy once a driver acquired minimal skill in advancing or retarding the spark. The hard part was cranking the T’s engine to life. It was prone to backfires, accounting for a good many fractured limbs over the years. For more, check out our feature "How to Drive a Model T."

We here at l'art et l'automobile have a passion for how the legendary automobiles of the past were envisioned, designed and built, just as intense as our passion for how they are celebrated and rendered into art and memorabilia. We would like to honor Ford's monumental achievement, bring the automobile to the mainstream consumer through the use of the assembly line, by sharing a little history on the subject, that will hopefully enlighten you just a little bit more on the amazing history of our shared love; the automobile.

Cheers and Happy Holidays,

Jacques Vaucher

Remember, this week we are hosting our Special 12 days of Christmas Online Auction, which opens for bidding December 1st at 12pm (noon) and Closes at noon on December 13th. This Auction contains many exciting, recently acquired pieces of Artwork, Memorabilia and Collectibles that would be perfect for filling your stockings or going under your tree this Holiday Season. Viewing has already begun at arteautoauction.com, so you definitely don't be a Grinch or you might get scrooged out of these amazing items.

Also, for great automotive artwork and memorabilia, don't forget to browse the many categories on our WEBSITE. Remember we also have many more items in our gallery, do not hesitate to contact us if you are looking for something in particular. Also be sure to check out our Newsfeed, which has details on our collection of Ford Artwork, and Memorabilia.

And as always, be sure to Like and Share on Facebook, Follow us on Twitter, or share a photo on Instagram.

And as always, be sure to Like and Share on Facebook, Follow us on Twitter, or share a photo on Instagram.