|

A Short history of a long race.

BY SAM POSE

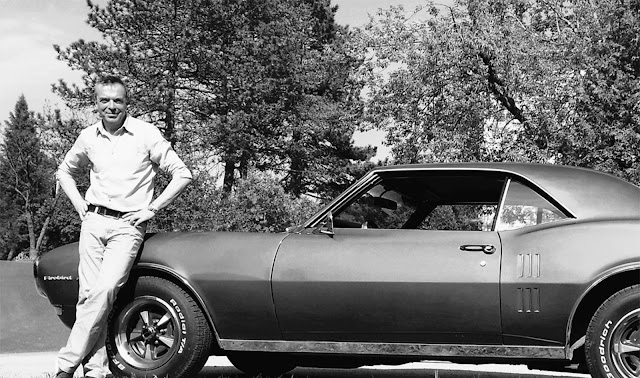

Dan Gurney had a 2-minute lead at Daytona when the engine blew in his Lotus 19. "I knew it was very close to the end of the race," Dan recalls, "so I put the clutch in and let the car roll up to the line, stopping a few feet short of it." The finish line was on a banked part of the track. "I stopped in the upper lane, next to the starter's stand. I even got out of the car for a moment—I don't know why. Then the starter began waving the checkered flag. I turned left and just coasted down the banking, across the line."

To win.

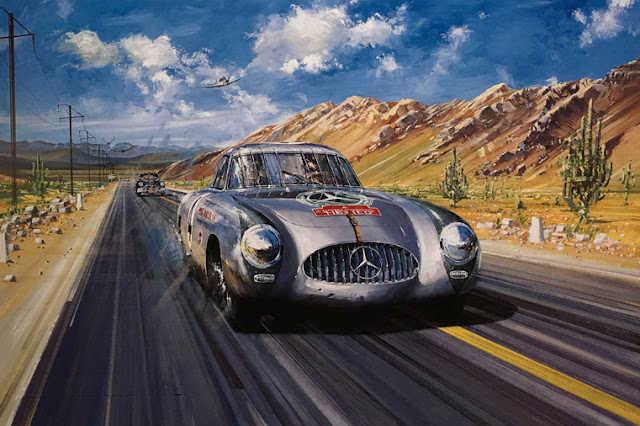

That unusual finish took place a half-century ago in the Daytona Continental, a forerunner to the 24-hour race first held four years later in 1966. The course was part banking, part infield road course—a configuration new to racing. Overnight, Daytona, Sebring and Le Mans became what was informally known as endurance racing's Triple Crown. It would be hard to conceive of three races whose ambience differed more. The 12 Hours of Sebring, in central Florida, was held amid the vacant hangars and rusting World War II bombers of a little-used airfield; Le Mans—the doyen of the three—combined extreme danger with the intoxicating beauty of a long twilight rush through the pastoral French countryside. Daytona was all about the banking. It was intended for stock cars, not the fragile long-distance racers, and it was brutal, pounding the suspensions and leaving the drivers feeling as if they had just been in the ring with Mike Tyson. Derek Bell, who won both Daytona and Le Mans, thought Daytona was tougher; the banking never let you rest.

|

| Ford GT40, photo courtesy of Road and Track |

Only the middle two of the four lanes were usable, the bottom one too rough and the top, next to the wall, slippery with dust in the early hours, then with marbles as the race wore on. The idea was that cars in the slower classes would keep to the lower lane, leaving the high line for the fast boys, but out there on the banking, etiquette gave way to spur-of-the-moment expediency. Drivers of slow cars couldn't see behind them any better than those in the fast cars. When a Camaro, say, pulled out to pass, it would block the lane for a prototype bearing down on the scene with a closing rate of up to 70 mph. A split-second to decide: high or low? Nine out of 10 times it was too late to get on the brakes, and if you did there was the risk of losing control—the suspension settings were compromised, the flat infield turns calling for spring rates and ride heights that were the exact opposite of what you wanted for the banking. So there you were, the car crushed down onto the bumpstops, veering from lane to lane, centrifugal force pinning you in the seat and trying to drag your hands off the wheel, going 200 and unable to see much of anything—that was the banking experience. Oh, and for 10 hours, you got to do it in the night.

|

| Dyson Riley & Scott Mk III, photo courtesy of Road and Track |

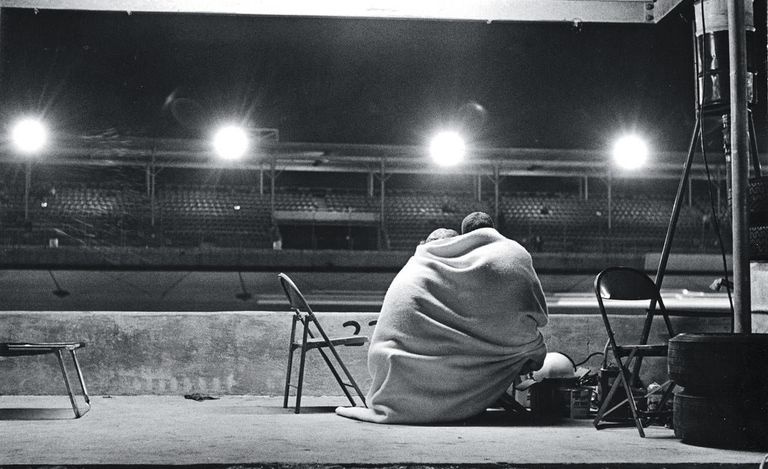

The Daytona night is the longest in racing and often the coldest. Florida in February can be damp and freezing—parka weather. Along pit lane, crews jury-rigged plastic curtains to block the wind—in the daytime it looked like Shantytown, but at night it was quite beautiful, the translucent walls glowing in the dark. Inside the enclosures, men slumped on the concrete floor, fighting to stay awake.

The contrast between the stands packed with cheering NASCAR fans at the 500 and the same stands at night, empty except for a few fanatics frozen in place like lumps of coal, left no room for doubt as to the relative popularity of stock cars versus sports cars. The first year of the 24-hour race, Daytona's management sought to evoke the carnival atmosphere of Le Mans with a Ferris wheel, but although it revolved all night, its neon tubes bright yellow on the spokes, it failed to attract any customers—because there weren't any customers to attract. Attendance at Le Mans was close to 300,000; in those first years at Daytona the oft-repeated joke was that the drivers outnumbered the spectators.

The contrast between the stands packed with cheering NASCAR fans at the 500 and the same stands at night, empty except for a few fanatics frozen in place like lumps of coal, left no room for doubt as to the relative popularity of stock cars versus sports cars. The first year of the 24-hour race, Daytona's management sought to evoke the carnival atmosphere of Le Mans with a Ferris wheel, but although it revolved all night, its neon tubes bright yellow on the spokes, it failed to attract any customers—because there weren't any customers to attract. Attendance at Le Mans was close to 300,000; in those first years at Daytona the oft-repeated joke was that the drivers outnumbered the spectators.

|

| 911 GT3 RS, photo courtesy of Road and Track |

Despite the poor attendance, the race became an important fixture on the international calendar. There was the cachet of the name Daytona (even then the 500 was a big deal), plus 1966 was the height of the Ford versus Ferrari battle, which lent historical significance to the proceedings. Ford swept the 1966 race, with Ken Miles and Lloyd Ruby coming home first in a GT40 Mk II. The following year, Ferrari fought back, winning with their stunning 330 P4s. In 1968, Porsche scored the first of its record 22 wins, and 1969 saw Roger Penske's battered Lola—a victim of a crash on the banking—eke out a win. This was big-time racing, and Speedway President Bill France chose to absorb the losses at the gate in return for the international prestige.

I was in those races, and I actually looked forward to Daytona—especially when I got to drive a Ferrari for NART (Luigi Chinetti's North American Racing Team). True, every stint involved some lurid moment on the banking, and if you weren't on the banking you were scrabbling through the tight, utterly featureless corners of the infield portion of the lap, but it was a chance to race the top European Formula 1 drivers, who in those days also participated in sports car racing. Jackie Ickx, Pedro Rodríguez, Jo Siffert, Chris Amon, Lorenzo Bandini—these men were heroes to me, and somehow the suffering imposed by Daytona helped forge a bond with them, a sort of Brotherhood of the Banking.

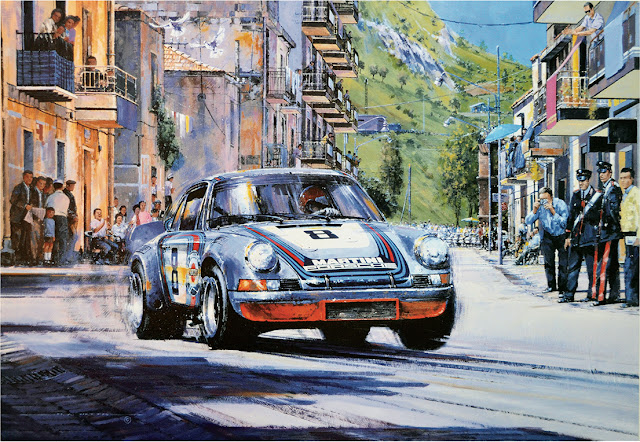

The epoch of the big 5-liter 917s and 512s ended with the 1971 season. The 1972 race, shortened to six hours, went to Ferrari's trim 3-liter sports racer—the last time the Ferrari factory would contest the race. The following year, 1973, saw a motley collection of sports racers upset by Peter Gregg's Porsche 911 RSR, which looked little different from the production 911s upon which it was based. Gregg was a brilliant but tightly wound Harvard grad who raced under the colors of Brumos Porsche, a dealership just up the road in Jacksonville. Peter's contacts at Weissach kept him a step ahead of the rest, but after the mighty prototypes and their swarms of engineers and mechanics, it was a letdown to see Daytona won by a car that looked as if it had just come from the showroom floor. Gregg's first victory was with Hurley Haywood, who would become the only driver to win Daytona five times. But it was Gregg, with four wins in five starts (including one for BMW), who defined an era—which ended with his suicide in 1980.

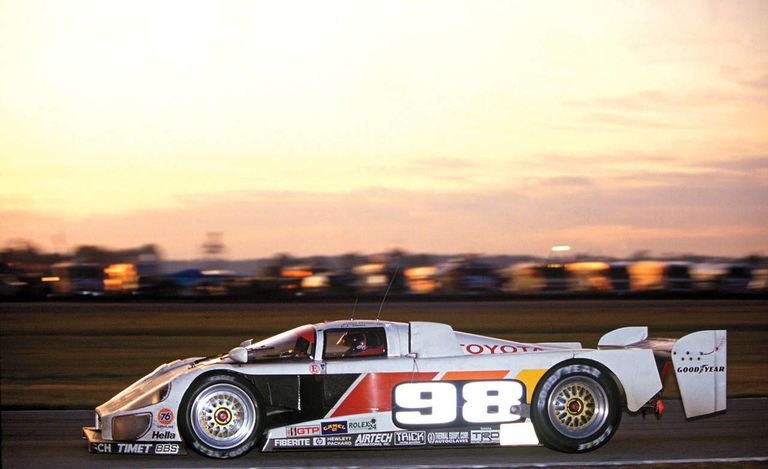

Through the 1980s, Porsche was the backbone of the race, and Daytona's prestige revived step by step as the German manufacturer supplied its many customers with ever faster cars—first the 935 and its derivatives, finally the superb Group C 962s, which were identical to the cars that were winning Le Mans. European aces such as Martin Brundle, Brian Redman and Rolf Stommelen filtered in along with Indy winners A.J. Foyt and Al Unser Jr. When Porsche finally had its fill of success, wins began going to such industry heavyweights as Jaguar, Nissan and Toyota, giving the race in the 1990s its second golden age. But only the factory-supported teams had a chance—the private teams were being driven out of the sport.

In 1999, the pressure for change was compelling enough to produce two new series, each backed by a man of great wealth and imagination. The American Le Mans Series, created by the inventor Don Panoz, established close ties with the French and adopted their rules. The other, sanctioned by the Grand American Road Racing Association, was the brainchild of Jim France. Jim was Bill France's son and part of the family's NASCAR dynasty, but he had a rogue gene: a passion for road racing. In 2000, Grand-Am took over Daytona's 24-hour classic and made it their marquee event. Both Panoz and France offered racing for prototypes and GT, but each took a different approach. Panoz's was caviar and champagne, while France's was burgers and beer.

Grand-Am promised NASCAR-style rules stability and rigid cost control—for example, no factory teams permitted and no in-season testing. The year 2003 saw the introduction of Daytona Prototype, a class with rules as tight as a spec series but open to a wide variety of engines, including Pontiac, Chevrolet, Lexus, Porsche and BMW. There were several chassis builders, too, of which Riley would become the most successful, winning at Daytona the last seven years. For safety and a better view of the banking, the rules mandated a bulbous greenhouse—and the big windshield, awkwardly mated to flat sides and a stubby nose, made for what most people agreed were ugly cars. But beauty is in the eye of the car owner, and the Daytona Prototype—and the prestigious series sponsor, Rolex, that went with it—was an attractive package. By 2006, 30 prototypes were on the grid for what was now called the Rolex 24. The GT cars did more than just fill out the fields; at first they were—embarrassingly—as fast as the new prototypes, forcing the organizers to invert the grid so as to have the prototypes up front at the start. A now-iconic Porsche 911 scored an upset victory, recalling the first win for Gregg and Haywood, exactly 30 years before.

Back in the 1960s and '70s, teams consisted of two drivers; today, in both GT and prototype classes, four drivers is the norm: the team's two regulars plus a big name NASCAR hero such as Jimmie Johnson or Jeff Gordon...or an Indy winner like Sam Hornish Jr. or Dario Franchitti—and there's still a spot open for a guy who pays big bucks for his ride. In 1997, the Rob Dyson entry set some kind of record when they won using seven drivers—I understand they were lining up spectators for a turn at the wheel when, mercifully, the race ended. (Just kidding, Rob.) Chip Ganassi's cars have won four times, including 2011 with Joey Hand, Graham Rahal, Memo Rojas and Scott Pruett—a formidable quartet, as good as any at Le Mans. The win was Scott's fourth; another and he'll tie Haywood.

The next generation of the Daytona Prototype, dubbed DPG3, will go into action at the 2012 Rolex. Their bodies will be allowed to have what is being called "brand character." For example: Alex Gurney and Jon Fogarty run a Chevrolet engine, and under the new rules they will be allowed to have a body that suggests a Corvette. I have seen some artists' renderings of the new look, and it's good.

Also in the works is a series-within-the-series. The idea is to link Daytona to shorter events at Indianapolis (over the weekend of the Brickyard 400) and Watkins Glen (a France-owned track), re-creating—after 40 years—a second Triple Crown, complete with its own prize money and points system. Instead of Daytona-Sebring-Le Mans, it will be Daytona-Indy-The Glen. Exciting? I think so.

The heart of the new Triple Crown will, of course, be Daytona, now entering its second half-century and well into its third golden era. A chicane near the end of the long back straight was intended to reduce the risk on the banking, but it seems Daytona's essential character never changes: The curbing is temporary (so it can be removed for NASCAR races), and slower cars drop their wheels over it, scattering gravel into the racing line, leaving the drivers of the faster cars to wonder if they may have a slow puncture on their hands. As John Andretti, who won in 1989, put it: "They just replaced one hazard with another."

When I think of Daytona, I think of a race that extracts a toll on anyone who enters it, a race in which winning has never come easily. It seems oddly appropriate, then, that Dan Gurney won the first race by coasting silently across the line.

As you may know, the Rolex 24 at Daytona will be run this weekend, January 26th-27th, which with the running of the Daytona 500 the week before, signals the start of Motor Racing Season. We here at l’art et l’automobile have been waiting as patiently as possible for racing season to start again, which admittedly has not been very patient, and Formula E just isn’t cutting it. That’s why we’re celebrating the beginning of the Racing Season, and in order to extend our celebrations to you, we have gathered all of our Daytona and Endurance Racing Artwork, Collectibles and Memorabilia and are presenting them to you. Please head over to our website and tour the Gallery and perhaps you can find an item that will assist in your celebration of the beginning of the Motorsports Season.

Enjoy the race and the season,

Jacques Vaucher

Remember we have a wide variety of items in our gallery, so do not hesitate to contact us if you are looking for something in particular.

And as always, be sure to Like and Share on Facebook, Follow us on Twitter, share a photo on Instagram and read our Newsfeed.

I was in those races, and I actually looked forward to Daytona—especially when I got to drive a Ferrari for NART (Luigi Chinetti's North American Racing Team). True, every stint involved some lurid moment on the banking, and if you weren't on the banking you were scrabbling through the tight, utterly featureless corners of the infield portion of the lap, but it was a chance to race the top European Formula 1 drivers, who in those days also participated in sports car racing. Jackie Ickx, Pedro Rodríguez, Jo Siffert, Chris Amon, Lorenzo Bandini—these men were heroes to me, and somehow the suffering imposed by Daytona helped forge a bond with them, a sort of Brotherhood of the Banking.

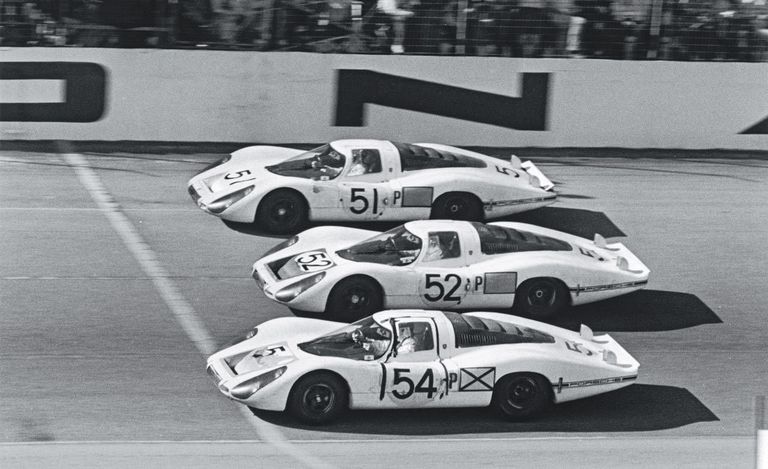

|

| Porsche 907, photo courtesy of Road and Track |

The epoch of the big 5-liter 917s and 512s ended with the 1971 season. The 1972 race, shortened to six hours, went to Ferrari's trim 3-liter sports racer—the last time the Ferrari factory would contest the race. The following year, 1973, saw a motley collection of sports racers upset by Peter Gregg's Porsche 911 RSR, which looked little different from the production 911s upon which it was based. Gregg was a brilliant but tightly wound Harvard grad who raced under the colors of Brumos Porsche, a dealership just up the road in Jacksonville. Peter's contacts at Weissach kept him a step ahead of the rest, but after the mighty prototypes and their swarms of engineers and mechanics, it was a letdown to see Daytona won by a car that looked as if it had just come from the showroom floor. Gregg's first victory was with Hurley Haywood, who would become the only driver to win Daytona five times. But it was Gregg, with four wins in five starts (including one for BMW), who defined an era—which ended with his suicide in 1980.

Through the 1980s, Porsche was the backbone of the race, and Daytona's prestige revived step by step as the German manufacturer supplied its many customers with ever faster cars—first the 935 and its derivatives, finally the superb Group C 962s, which were identical to the cars that were winning Le Mans. European aces such as Martin Brundle, Brian Redman and Rolf Stommelen filtered in along with Indy winners A.J. Foyt and Al Unser Jr. When Porsche finally had its fill of success, wins began going to such industry heavyweights as Jaguar, Nissan and Toyota, giving the race in the 1990s its second golden age. But only the factory-supported teams had a chance—the private teams were being driven out of the sport.

|

| Dan Gurney's Eagle, photo courtesy of Road and Track |

In 1999, the pressure for change was compelling enough to produce two new series, each backed by a man of great wealth and imagination. The American Le Mans Series, created by the inventor Don Panoz, established close ties with the French and adopted their rules. The other, sanctioned by the Grand American Road Racing Association, was the brainchild of Jim France. Jim was Bill France's son and part of the family's NASCAR dynasty, but he had a rogue gene: a passion for road racing. In 2000, Grand-Am took over Daytona's 24-hour classic and made it their marquee event. Both Panoz and France offered racing for prototypes and GT, but each took a different approach. Panoz's was caviar and champagne, while France's was burgers and beer.

Grand-Am promised NASCAR-style rules stability and rigid cost control—for example, no factory teams permitted and no in-season testing. The year 2003 saw the introduction of Daytona Prototype, a class with rules as tight as a spec series but open to a wide variety of engines, including Pontiac, Chevrolet, Lexus, Porsche and BMW. There were several chassis builders, too, of which Riley would become the most successful, winning at Daytona the last seven years. For safety and a better view of the banking, the rules mandated a bulbous greenhouse—and the big windshield, awkwardly mated to flat sides and a stubby nose, made for what most people agreed were ugly cars. But beauty is in the eye of the car owner, and the Daytona Prototype—and the prestigious series sponsor, Rolex, that went with it—was an attractive package. By 2006, 30 prototypes were on the grid for what was now called the Rolex 24. The GT cars did more than just fill out the fields; at first they were—embarrassingly—as fast as the new prototypes, forcing the organizers to invert the grid so as to have the prototypes up front at the start. A now-iconic Porsche 911 scored an upset victory, recalling the first win for Gregg and Haywood, exactly 30 years before.

|

| Dale Earnhardt's Corvette, photo courtesy of Road and Track |

Back in the 1960s and '70s, teams consisted of two drivers; today, in both GT and prototype classes, four drivers is the norm: the team's two regulars plus a big name NASCAR hero such as Jimmie Johnson or Jeff Gordon...or an Indy winner like Sam Hornish Jr. or Dario Franchitti—and there's still a spot open for a guy who pays big bucks for his ride. In 1997, the Rob Dyson entry set some kind of record when they won using seven drivers—I understand they were lining up spectators for a turn at the wheel when, mercifully, the race ended. (Just kidding, Rob.) Chip Ganassi's cars have won four times, including 2011 with Joey Hand, Graham Rahal, Memo Rojas and Scott Pruett—a formidable quartet, as good as any at Le Mans. The win was Scott's fourth; another and he'll tie Haywood.

The next generation of the Daytona Prototype, dubbed DPG3, will go into action at the 2012 Rolex. Their bodies will be allowed to have what is being called "brand character." For example: Alex Gurney and Jon Fogarty run a Chevrolet engine, and under the new rules they will be allowed to have a body that suggests a Corvette. I have seen some artists' renderings of the new look, and it's good.

|

| Daytona at night, photo courtesy of Road and Track |

Also in the works is a series-within-the-series. The idea is to link Daytona to shorter events at Indianapolis (over the weekend of the Brickyard 400) and Watkins Glen (a France-owned track), re-creating—after 40 years—a second Triple Crown, complete with its own prize money and points system. Instead of Daytona-Sebring-Le Mans, it will be Daytona-Indy-The Glen. Exciting? I think so.

The heart of the new Triple Crown will, of course, be Daytona, now entering its second half-century and well into its third golden era. A chicane near the end of the long back straight was intended to reduce the risk on the banking, but it seems Daytona's essential character never changes: The curbing is temporary (so it can be removed for NASCAR races), and slower cars drop their wheels over it, scattering gravel into the racing line, leaving the drivers of the faster cars to wonder if they may have a slow puncture on their hands. As John Andretti, who won in 1989, put it: "They just replaced one hazard with another."

When I think of Daytona, I think of a race that extracts a toll on anyone who enters it, a race in which winning has never come easily. It seems oddly appropriate, then, that Dan Gurney won the first race by coasting silently across the line.

As you may know, the Rolex 24 at Daytona will be run this weekend, January 26th-27th, which with the running of the Daytona 500 the week before, signals the start of Motor Racing Season. We here at l’art et l’automobile have been waiting as patiently as possible for racing season to start again, which admittedly has not been very patient, and Formula E just isn’t cutting it. That’s why we’re celebrating the beginning of the Racing Season, and in order to extend our celebrations to you, we have gathered all of our Daytona and Endurance Racing Artwork, Collectibles and Memorabilia and are presenting them to you. Please head over to our website and tour the Gallery and perhaps you can find an item that will assist in your celebration of the beginning of the Motorsports Season.

Enjoy the race and the season,

Jacques Vaucher

Remember we have a wide variety of items in our gallery, so do not hesitate to contact us if you are looking for something in particular.

And as always, be sure to Like and Share on Facebook, Follow us on Twitter, share a photo on Instagram and read our Newsfeed.